[ad_1]

That is an version of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly information to one of the best in books. Join it right here.

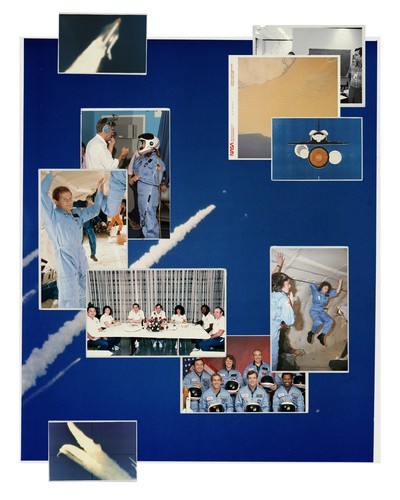

There have been moments in Adam Higginbotham’s new guide Challenger that made me gasp and flip to the endnotes. I wasn’t trying to discover the story’s denouement—I already knew what occurred on the morning of January 28, 1986: The area shuttle Challenger broke aside simply over a minute into its voyage, killing all seven astronauts aboard. However Higginbotham had so absolutely reconstructed the occasions, together with the internal ideas of people that died practically 40 years in the past, that whereas writing concerning the guide, I simply wanted to reply the query: How may he probably know that? How may he relay what was occurring in NASA’s disparate hubs in Texas, Alabama, and Florida? And the way may a venture like this one, printed 38 years after the disaster, add new insights to what already exists?

First, listed here are 4 new tales from The Atlantic’s Books part:

The quick solutions lie principally ultimately matter. There, Higginbotham reveals that he relied on intensive interviews with surviving household of the Challenger crew, along with supporting materials from engineers, contractors, and astronauts. He mentions 4 years of trawling via archives and oral histories, submitting FOIA requests, sending emails, and speaking with folks; the notes within the completed guide are 63 pages lengthy, in tiny script, and adopted by a strong bibliography. Higginbotham had ample materials to drag from—many diagrams, experiences, and testimonies exist as a result of the catastrophe was coated extensively from practically the second the shuttle disappeared in a ball of orange flame and white vapor. What he provides is depth made attainable by time.

The creator himself notes that a lot of the out there writing about Challenger is extraordinarily technical, and that his goal was to inform a human story. His descriptions of the astronauts, their households, their emotions, and their grumbles, quirks, and beliefs, made me assume at occasions of the work of the author Alex Kotlowitz, whose books—comparable to his lauded exploration of life in Chicago’s Henry Horner Properties, There Are No Youngsters Right here—recount the minute-by-minute ideas and emotions of their topics. I took a category with Kotlowitz on narrative nonfiction after I was an undergrad, and discovered that the sorts of minute particulars that make a narrative come alive are unlocked over time—time spent together with your topics, asking them questions, attending to know them, turning broad sketches of character into absolutely realized folks. And the expertise of studying Challenger made me consider different nonfiction that baffled me with faithfully reconstructed element—Katherine Boo’s Behind the Lovely Forevers, Anne Fadiman’s The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, David Quammen’s The Tune of the Dodo.

However Challenger additionally highlights one thing else that’s beneficial: the advantage of the lengthy view. Higginbotham’s guide merely couldn’t have existed years in the past. Maybe the sources would have been much less amenable to speaking; the opposite books he learn to tell his work hadn’t but been written. His construction—starting with one in all NASA’s first deadly disasters, the Apollo 1 fireplace, and ending with the newest deaths of NASA astronauts, aboard the Area Shuttle Columbia in 2003—wouldn’t have been attainable. And the Columbia accident is a morbid however good coda to the guide, highlighting simply what number of classes the company did not be taught from its earlier disaster.

The tragedy recounted on this guide stays as potent because it was in 1986. The variety of possibilities there have been to save lots of lives may even make it extra painful to revisit. However for a author, time provides understanding, and it provides weight. Challenger just isn’t forgotten, and neither are its passengers, particularly the high-school instructor Christa McAuliffe. However its classes about resisting stress and complacency, and about technological progress’s reliance on the human beings working the tech, are particularly vital in a world of fascinating, hazardous innovation.

What the Challenger Catastrophe Proved

By Emma Sarappo

We take the workings of extensive, difficult technological programs on religion. However they rely upon folks—and, generally, folks fail.

What to Learn

Flying Blind, by Peter Robison

In 2018 and 2019, 346 folks died in two crashes of malfunctioning Boeing 737 MAX 8 planes. Robison’s investigation into the tragedies asks: How did probably the most revered engineering corporations in America produce such fatally flawed plane? This account covers the lengthy arc of Boeing’s historical past and locations the blame squarely on the company tradition that arose after a merger within the late Nineties, which targeted on enriching shareholders on the expense of cautious engineering. Over the 737 MAX 8’s improvement, cost-cutting fixes piled up with agonizing implications: Not solely had Boeing’s workers created software program that resulted in management being wrested from pilots due to a steadily defective instrument’s alerts; additionally they deleted related elements of the airplane’s flight handbook, and maintained that costly flight-simulator coaching wasn’t needed for the brand new plane. What makes the account riveting, although—and blood-boiling—is Robison’s consideration to the tales of the victims and their grieving households. Studying them, one finally ends up emotionally invested within the workings of economic aviation, and freshly conscious of the good complexity and duty underlying an trade that so many people rely upon to work, journey, and see distant family members. — Chelsea Leu

From our record: Eight books that specify how the world works

Out Subsequent Week

📚 Any Individual Is the Solely Self, by Elisa Gabbert

📚 The Nice River, by Boyce Upholt

📚 Hip-Hop Is Historical past, by Questlove with Ben Greenman

Your Weekend Learn

Animal Habits’s Greatest Taboo Is Softening

By Katherine J. Wu

“The stress to keep away from anthropomorphism in any respect prices has lessened,” [Joshua] Plotnik advised me. His present research on elephants, which delve into ideas comparable to cognition and intelligence, would most likely have gotten him laughed out of most psychology departments a number of many years in the past. Now, although, many teachers are comfy describing his examine animals as intelligent, cooperative, and able to pondering and feeling. This extra permissive atmosphere does put that rather more stress on researchers to weigh precisely how and the place they’re making use of anthropomorphism—and to take action responsibly. But it surely’s additionally an vital alternative “to make use of our anthropomorphic lens rigorously,” Kwasi Wrensford, a behavioral biologist on the College of British Columbia, advised me.

Whenever you purchase a guide utilizing a hyperlink on this e-newsletter, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.

Discover all of our newsletters.

[ad_2]