[ad_1]

You can’t stroll far in Tel Aviv with out encountering a uncooked expression of Israel’s nationwide trauma on October 7. The streets are lined with posters of hostages, and big indicators and graffiti demanding BRING THEM HOME. Making my approach via Florentin, a former slum that has change into an artists’ neighborhood, to go to Zoya Cherkassky-Nnadi, one of the vital widespread painters in Israel, I handed a mural of a kid being taken hostage. A Hamas terrorist in a inexperienced headband and balaclava factors a rifle on the youngster, who has his palms within the air. The boy is recognizable as a model of the kid within the well-known {photograph} from the Warsaw Ghetto rebellion in 1943. The artist first painted the mural in Milan, however photographs of October 7 are usually not at all times nicely obtained outdoors Israel. In Milan, somebody scrubbed the Jewish youngster out of the image.

Zoya—first title solely, not less than within the artwork world—additionally made drawings about October 7 that met with an unexpectedly hostile response overseas. Till then, Zoya’s worldwide repute had been ascending. She was seen as a pointy critic and satirist of Israeli society—Israel’s Hogarth, because it had been. Like him, she sketches individuals whom others overlook; like his, her portraits editorialize. Maybe you assume that missed means “Palestinian.” Zoya has made work in regards to the plight of Palestinians, however what actually pursuits her are even much less seen members of Israeli society, equivalent to African immigrants, and the invisible and stigmatized, equivalent to intercourse staff. Since her October 7 drawings had been proven in New York, nonetheless, she has been accused of creating propaganda for Israel. Comparable expenses have been leveled towards different distinguished Israeli artists for the reason that begin of the Gaza warfare, however the denunciation of Zoya was notably public.

Zoya is an immigrant herself—born in Kyiv in 1976, when Ukraine was nonetheless a part of the Soviet Union—and he or she has spent her life in a type of inside exile. In Kyiv, she was a Jew. In Israel, she’s a goy (non-Jew), not less than by rabbinic requirements, as a result of her mom isn’t Jewish, by the identical requirements. (Zoya’s father was Jewish, and so was her mom’s father.) She is married to an much more current immigrant, Sunny Nnadi, who comes from Nigeria. She used to vote for the far-left, Arab-majority political celebration Hadash, however stopped when it, together with a coalition of comparable events, sided with Vladimir Putin in Russia’s warfare on Ukraine. She has the phrase ATTITUDE tattooed on her left forearm, in English. Her artwork checks the boundaries of the permissible. When Zoya had a serious solo present in 2018 on the Israel Museum, one of many nation’s preeminent establishments, the newspaper Haaretz famous the incongruity of the museum’s embrace of Israel’s “everlasting dissident.”

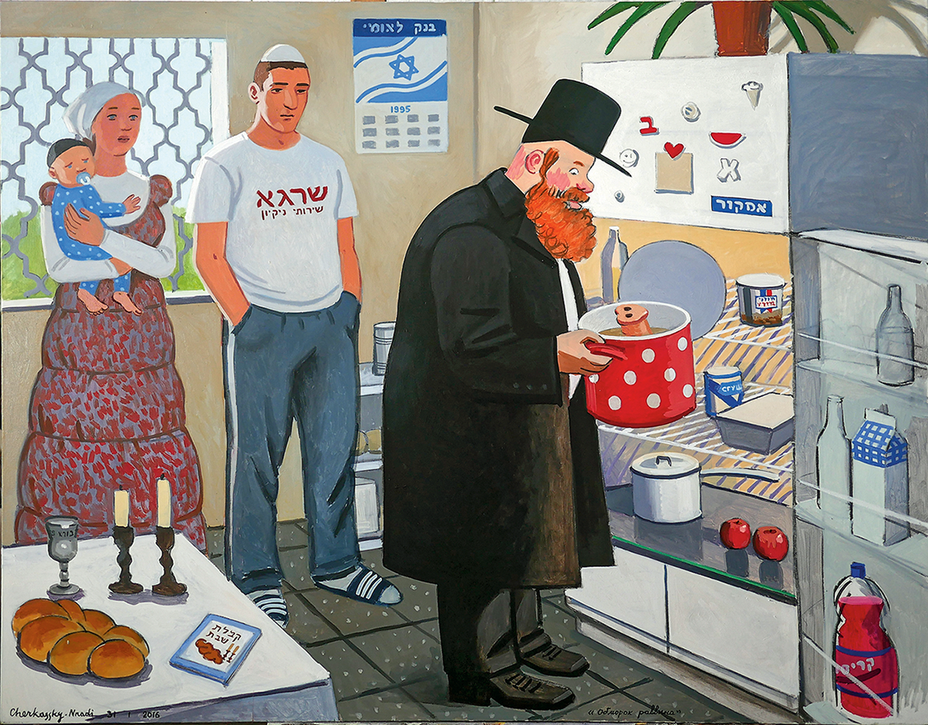

That exhibition, which was referred to as “Pravda,” depicted Soviet and post-Soviet immigrants struggling to acclimate to an unfriendly Israel. Two work, for instance, lampoon the rabbinic authorities who implement non secular regulation. Lots of the million or so new arrivals had by no means stored kosher or been circumcised, and roughly 1 / 4 of these weren’t thought of Jews by Israel’s rabbinic institution, normally as a result of their moms, like Zoya’s, weren’t Jewish. A handful selected to bear Orthodox conversions.

That’s the backdrop for The Rabbi’s Deliquium, which is about within the residence of two younger Russian converts to Orthodox Judaism. The scene is just half fantastical. The person wears a kippah and his spouse’s hair is roofed. Their child’s head can also be lined—by an enormous kippah. (In actual life, infants don’t put on kippahs.) A rabbi is inspecting their kitchen to determine whether or not they’re actually retaining kosher; this sort of factor really happens. He lifts the lid of a pot and finds himself face-to-face with an enormous pig snout. Deliquium means a sudden lack of consciousness. We all know what’s going to occur to the rabbi subsequent.

Within the second portray, The Circumcision of Uncle Yasha, two ultra-Orthodox rabbis in blood-splattered scrubs carry out the operation in a pool-blue working room. One wields a pair of scissors whereas Uncle Yasha appears down at his penis in terror. The opposite rabbi covers his face with a e book labeled TORAH, as non secular Jews typically do with their prayer books, however on this case the gesture suggests a refusal to see. Within the nook of the working room lies a kidney dish full of blood. The scene evokes the notorious anti-Semitic blood libel, wherein Jews are mentioned to empty the blood of a Christian youngster to make use of of their Passover matzah. The present’s curator, Amitai Mendelsohn, understates the allusion’s outrageousness when he calls it “barely unsettling” within the catalog. The portray is so sacrilegious, it’s humorous—admittedly, it’s additionally a Jewish in-joke that may most likely work much less nicely outdoors Israel, the place a mordant reference to a slander that resulted within the deaths of numerous Jews would possibly nicely come throughout as merely distasteful.

Zoya’s October 7 drawings are usually not humorous in any respect. Days after the invasion, having taken her terrified 8-year-old daughter to Berlin, Zoya started placing on paper the scenes of horror that wouldn’t cease tormenting her. She first posted her drawings on social media. Quickly they had been being projected onto the white facade of the Tel Aviv Museum of Artwork from “Hostages Sq.,” the plaza in entrance of that constructing, which has change into a website for public artwork and protest in regards to the kidnapped. The Jewish Museum introduced the drawings to New York, the place Zoya occasioned a narrative in The New York Instances, amongst different retailers, not on account of her art work, precisely, however as a result of she was heckled and did one thing uncommon in response.

The incident occurred in February, and a few of it was recorded on telephones. Zoya and the museum’s director, James Snyder, are about to have a dialog onstage when younger activists in black surgical masks arise and start to shout. As they’re hustled out, one other group rises and yells from printed scripts: “As cultural staff, as anti-Zionist Jews of conscience, as New York Metropolis residents, we implore you to confront the truth of”—boos and cries of “Shut up” from the viewers drown out their phrases. Clearly, the Jewish Museum crowd just isn’t on the facet of the protesters. Guards forcibly take away the second group of disrupters.

Immediately, cheers erupt close to the stage and Zoya comes into view, a big, long-haired, makeup-free girl in a stretchy grey gown and black boots, sitting calmly, apparently unfazed. It’s important to learn the information accounts to study what had simply occurred off-screen: Zoya had mentioned, merely, “Fuck you.”

When extra protesters had been escorted out and the drama had subsided, Zoya caustically noticed, “I’m very, very pleased that there are privileged younger individuals from privileged nations that may understand how all people on the planet ought to act.”

The protesters had additionally given out flyers with an insulting caricature of “The Zionist Artist at Work,” displaying an artist in fight gear portray a missile. Based on an Instagram publish by a gaggle referred to as Writers Towards the Battle on Gaza, the activists accused the Jewish Museum of collaborating in “violent Palestinian erasure” as a result of Zoya had failed to incorporate the Palestinian victims of the Gaza warfare within the present. Zoya’s fast response to that cost was that she could but make artwork in regards to the Palestinian victims. “Simply because I’ve compassion for individuals within the kibbutz doesn’t imply I don’t have compassion for individuals in Gaza,” she informed the Instances.

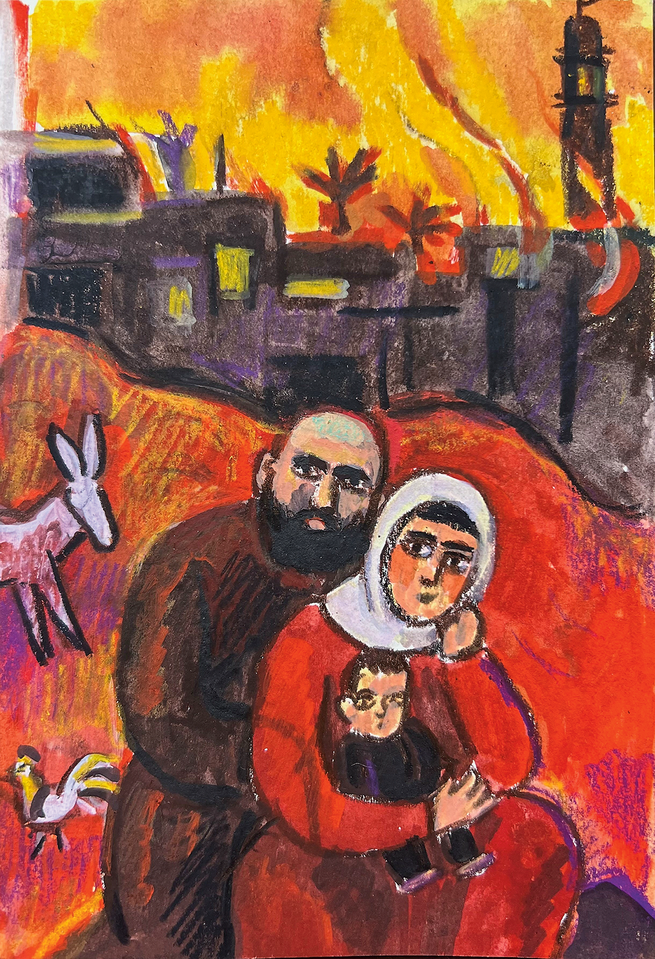

Zoya has addressed Israeli cruelty towards Palestinians previously. A 2016 portray referred to as The Historical past of Violence exhibits a uniformed Israeli soldier guarding two handcuffed males stripped all the way down to their underwear, presumably Palestinians. After Pogrom (2023) portrays a pair and youngster in entrance of their burning residence, an obvious reference to the 2023 settler rampage within the Palestinian village of Huwara, within the West Financial institution. It reworks a World Battle II–period portray by Chagall, The Ukrainian Household, about Jews in an analogous scenario, as if to say, Who’s committing the pogroms now?

Not everybody within the viewers on the Jewish Museum opposed the protest. In an article largely sympathetic to the activists, the net artwork journal Hyperallergic quoted an nameless spectator saying that the viewers’s hostile response to the protest was “chilling.” Two months after the incident, Zoya posted the next on Instagram: “The Central Committee of the CPSU”—the Communist Get together of the Soviet Union—“allowed extra freedom of creative expression than [the] up to date artwork world.”

In late Could, I requested Zoya what she thought in regards to the melee now, particularly that “Fuck you.” Each facet of her look says I don’t have time for this nonsense : her single-color stretch attire (she was sporting black that day), her Velcroed sandals, her blunt bangs, her black rectangular glasses. We had been at a printmaking studio in Jaffa that had invited her to discover ways to make monotype prints. The method includes portray on a big piece of plastic, then taking an impression. She was turning a portray of hers right into a black-and-white model of itself, utilizing broad, assured strokes, and he or she didn’t cease as she answered my query. “I feel this was precisely the extent of dialogue applicable for this case,” she mentioned.

Zoya’s collection 7 October 2023 deserves a spot within the canon of artwork about warfare. Twelve small, meticulous drawings in pencil, marker, crayons, and watercolor type a mournful martyrology. The backgrounds are flat black and the colours are somber, aside from violent reds and oranges that reappear in a number of works and typically burst into red-orange flames. Zoya makes use of an easy-to-parse visible language, half grim youngsters’s-book illustration, half German Expressionism: You are feeling Max Beckmann, one in every of her favourite artists, within the slashing strains, darkened hues, and unflinching but someway non secular representations of horror. “I’m quoting historic work that depict struggling,” she informed me. She needed their assist channeling the ache “so I’m not alone on this collection.”

Zoya portrayed victims solely; perpetrators are nowhere to be seen. With one exception—a drawing of kid hostages—she didn’t reproduce the faces of precise individuals. Her figures are all sharp angles and outsize oval eyes. In a drawing in regards to the Nova music competition, the place tons of of Israeli concertgoers had been killed, the sticklike higher arms of the younger individuals working from their murderers stretch out whereas their forearms slant up towards heaven and their calves kick out behind them. The staccato repetition of limbs and palms and toes turns the scene right into a dance of dying. Two drawings do disturbing issues with heads. In Bloodbath of the Innocents, based mostly on the Giotto fresco of the identical title, murdered youngsters lie heaped on the bottom, and you may depend extra heads than our bodies (some our bodies could also be blocking our view of others, however the impact remains to be eerie). In Zoya’s rendering of a rape sufferer mendacity face down in blood, her head has turned too far to the facet, like a damaged doll’s, and her empty eye sockets stare on the viewer.

Israelis gave me unusual appears once they realized that I’d come all the best way from New York to jot down a profile of an artist. In the midst of a warfare? Possibly I used to be actually writing in regards to the cultural boycott? That too, I mentioned. Many Israelis within the arts and academia dread the anti-Israel fury—or not less than the worry of protest—that’s making curators, gallerists, arts programmers, publishers, college division heads, and organizers of educational conferences loath to ask Israeli individuals. Being shut out of worldwide venues is a continuing subject. For 20 years, the Palestinian-founded Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) motion and the Palestinian Marketing campaign for the Educational and Cultural Boycott of Israel have pressured cultural organizations world wide to exclude Israelis, with combined outcomes.

However now the mission is succeeding. The Israeli visible artists I talked with really feel that the world turned on them in a day—on October 19, to be exact, when Artforum revealed an open letter signed by 4,000 artists and intellectuals calling for a cease-fire, an finish to violence towards civilians, and humanitarian help for Gaza. To the outrage of Israelis and lots of Jews elsewhere, the unique model of the letter failed to say that Hamas’s atrocities had began the warfare—or to say Hamas in any respect.

A month earlier than I arrived in late spring, Ruth Patir, the artist chosen to signify Israel within the Venice Biennale, introduced that her present would stay closed till there was a cease-fire and the hostages had been launched. The message, relayed a day earlier than the press preview of the Israeli pavilion, was idealistic but in addition strategic: It had change into clear that protests would block Israel’s pavilion. I went to see Mira Lapidot, the chief curator of the Tel Aviv Museum of Artwork, who helped grasp the present in Venice and took part within the choice to cancel it. She has deep reservations about the best way the warfare is being performed, however she was shocked that individuals within the arts, of all fields, would fail to acknowledge that “an individual just isn’t their authorities and never their state, that persons are multifaceted, have totally different views, that there’s a place for individuality. It’s all utterly simply worn out.”

No much less unnerving than the cancellations are the alternatives that dematerialize: the once-friendly museum director who not calls, the dance firm that may’t appear to e book its ordinary excursions. Once I requested Israeli artists whether or not they had any upcoming exhibits overseas, I discovered that in the event that they mentioned sure, very possible the present can be in one in every of three locations: a Jewish-owned gallery, a Jewish museum, or Germany, the place strict legal guidelines prohibit anti-Semitic exercise. (In June, Germany’s federal intelligence company labeled BDS as a “suspected extremist group.”) Artists from overseas are additionally staying away from Israel. Kobi Ben-Meir, the chief curator on the Haifa Museum, informed me that he used to have the ability to speak reluctant artists into displaying their work there; now, in the event that they take his calls, they are saying Let’s speak in a 12 months or so. “We’re type of like in a ghetto proper now, right here and in addition internationally,” Maya Frenkel Tene, a curator on the Rosenfeld Gallery, which represents Zoya in Israel, informed me. “A Jewish ghetto.”

Zoya being Zoya, she waved off my questions on boycotts. Being boycotted just isn’t like having your own home bombed, she mentioned—and that, in flip, just isn’t as unhealthy as being in Gaza, she added. Later, she informed me that she wished boycotts had been her downside. What’s your downside, then? I requested. “What to do to keep away from the Holocaust,” she mentioned. Did she imply what would occur if Hamas or Hezbollah overran Israel? “It’s not solely Hamas and Hezbollah. The scariest half is what is occurring inside Israel,” she mentioned, “these loopy right-wing Israelis” who assault humanitarian help convoys and terrorize Palestinians within the West Financial institution.

Zoya deplores the coalition governing her nation, however about Gaza, she mentioned, “I’m jealous of people that know what’s the proper factor to do. I do not know.” Like virtually everybody I met in Israel, she questioned whether or not she and her household must depart; she and Sunny have thought of going to his village in Nigeria, however violence roils that nation too.

Zoya’s dismissiveness however, the boycotts are worrisome, and never simply because they search to censor the artwork of a whole nation. Zoya’s work specifically is a reminder of what can be misplaced. Her artwork provides the world an opportunity to study in regards to the richly sophisticated actuality beneath the schematic image of Israel as a society of oppressors and oppressed that’s all too typically disseminated by anti-Zionists. Zoya’s artwork shouldn’t be outlined by the October 7 collection alone. She is prolific and protean, and people drawings are usually not essentially her greatest work. When she arrived on the Israeli artwork scene in her early 20s, she was precociously subtle. Over the course of practically three many years, she has made unforgettable artwork about artwork and searing artwork about society, and mastered a outstanding array of genres: manga, digital artwork, Jewish liturgical texts, even Soviet Socialist Realism, whose biggest artists she is decided to rescue from the trash heap of Western artwork historical past. “She will do something and every thing in artwork,” Gideon Ofrat, a distinguished historian of Israeli artwork, informed me. “She doesn’t repeat herself. She at all times develops a brand new type and a brand new language, and every thing she touches is finished expertly from a technical viewpoint.”

What unites Zoya’s eclectic physique of labor is her supremely jaded and really Soviet sarcasm—and an empathy for her topics that has deepened through the years. “It’s straightforward to be ironic as an artist, however it isn’t straightforward to be humorous,” Ben-Meir, the Haifa Museum curator, mentioned of Zoya. Stupidity or hypocrisy or ideological rigidity prompts her inside shock jock—in her artwork, and in individual. As of late she will get quite a lot of her comedian materials from postcolonialist lingo. As soon as, as we had been leaving her studio, a shrieking sound got here from someplace within the constructing. What on earth is that? I requested. Wild parrots, Zoya answered. Parrots had been delivered to Israel as pets however escaped and reproduced; now they occupy all of Tel Aviv. “They don’t seem to be indigenous to this land,” she noticed. “Genocidal settler parrots!”

When the 14-year-old Zoya realized in 1991 that her household had lastly obtained permission to maneuver to Israel—because it occurs, they left two weeks earlier than the autumn of the Soviet Union—she was excited: She would lastly have entry to all of the Western tradition forbidden to her, like music and artwork. But she had already been finding out for 4 years in top-of-the-line artwork faculties within the Soviet Union, a nation that supplied extra rigorous coaching within the methods of educational realism than every other nation, and when her trainer informed her that artwork college students in Israel didn’t grasp the identical abilities, she cried. “I believed, I’ll by no means discover ways to draw,” she informed me. She bought into one of many high Israeli excessive faculties specializing in artwork and located that the scholars’ draftsmanship certainly lagged behind hers. She had her associates again residence ship her their homework assignments and did them on her personal.

Zoya belongs to a cohort of younger émigrés from the previous Soviet Union generally known as the “1.5 era,” the primary set of kid immigrants in Israel who didn’t assimilate the best way youngsters normally do. The muscular sabra perfect by no means appealed to them; once they grew up, they held on to their hybrid id, Liza Rozovsky, a reporter at Haaretz initially from Moscow, informed me. The “Russians”—“in Israel they did change into ‘Russian’ hastily, despite the fact that most of them didn’t even come from Russia,” she famous—had their very own faculties, their very own theater and music-enrichment courses. Lacking their biscuits, muffins, and really nonkosher sausages, they opened grocery shops that stocked Russian manufacturers. The kids had been depressing at first: They dressed improper, ate funny-smelling sandwiches at school, and had been bullied. Pleasure got here later, Rozovsky mentioned. The teenage Zoya did superb. “I used to be within the artwork bubble,” she defined. However she registered the unhappiness round her.

The Russians didn’t match into the Western racial classes typically used to categorise Israelis—white Ashkenazi overclass on the highest; darkish Mizrahi, or Center Jap, underclass on the underside—as a result of they had been white and Ashkenazi, but rungs beneath better-integrated Israelis socially; nobody knew what to make of them. No matter superior levels and white-collar jobs they might have had within the Soviet Union, now they labored as cleansing women and evening guards. The run-down neighborhoods they moved into had beforehand been the area of the Mizrahi Jews, and the 2 low-status teams engaged in a warfare of mutual condescension. The Mizrahim thought that Russian males had been pale and unmanly and that Russian ladies had been all prostitutes. Zoya remembers Israeli boys taunting Russian ladies by calling out “5 shekels!,” that means 5 shekels for intercourse. For his or her half, the Russians thought of the Mizrahim—certainly, most Israelis—loud, uncultured boors.

Russians didn’t match into the Israeli artwork world, both. In Nineties Israel, realism was reactionary, passé. “It was embarrassing to know the right way to paint, however much more embarrassing to know the right way to paint like a Russian,” Zoya mentioned in a gallery speak in 2017. Good artists—critical artists—made summary, conceptual, mental items. Cultural gatekeepers had been Ashkenazi. There have been virtually no Russian gallery house owners or curators. Zoya studied on the HaMidrasha College of Artwork at Beit Berl Faculty, generally known as a house for avant-garde, nonrepresentational artists. The poststructuralist curriculum irritated her. She couldn’t make sense of subversive French thinkers equivalent to Georges Bataille and Jacques Lacan, as a result of she wasn’t acquainted with the discourses they had been subverting; that made her really feel ashamed. To the good chagrin of her mom, she by no means graduated. “I’m not a thinker, and I didn’t go research artwork as a result of I would like philosophy,” she informed me. “I like portray.”

Zoya didn’t change into a painter instantly. She made conceptual works whose level gave the impression to be that they had been amusing to make. An early collaboration with a classmate concerned flying to Scotland with a light-weight, human-size sculpture of a good friend in what regarded like a physique bag—U.Ok. customs officers had been flummoxed—after which taking the “good friend” into the forest, the place they posed him in numerous positions and photographed him. Don’t ask what the purpose was: They had been 19. “At this age, you possibly can’t actually clarify what the hell it means,” Zoya mentioned.

Her breakthrough got here in 2002 with a solo present referred to as “Collectio Judaica.” It was the product of an excellent deal extra thought and care. Like “Pravda” 15 years later, it will most likely not do nicely outdoors Israel; its angle towards Jewishness is much more open to misinterpretation.

The present largely consisted of Jewish objects, all completely designed and executed by Zoya. Nevertheless it was not a easy celebration of Jewish materials tradition. Among the gadgets had been conventional: a Passover Haggadah, two porcelain seder-plate units, and 4 mizrach gouache work (a mizrach hangs on the jap wall of an observant Jewish residence with a purpose to orient prayer). However different fabrications had been, nicely, sui generis. Within the gallery window lay three brooches, all 18-karat-gold replicas of the yellow material Star of David that the Nazis made Jews put on, full with the phrase Jude within the center. A Tel Aviv council member within the pro-settler Nationwide Non secular Get together heard in regards to the present and demanded that the mayor and Israel’s lawyer common shut it. Her effort failed. The present was successful.

Why would anybody flip one of the vital despised symbols of anti-Semitism into jewellery and show it as if it had been a Jewish treasure? The seemingly weird enterprise encapsulated the elemental gesture of the present. “I feel that is crucial work Zoya did ever,” Zaki Rosenfeld, her gallerist in Israel, informed me. (Since 2019, Zoya has additionally been represented by the Fort Gansevoort gallery, in New York.) Zoya was erasing the road between the sacred and the vile, the Jewish artifact and the anti-Semitic picture, then sharpening the ensuing monstrosities to a really excessive shine.

The inspiration for “Collectio Judaica” got here from a mug within the form of a hooked-nosed Jew, which Zoya present in an antiques retailer in Tel Aviv. “I requested the vendor, ‘How a lot is the anti-Semitic cup?’ ” she informed me. “And he mentioned, ‘Why do you suppose it’s anti-Semitic?’ For me it was apparent it’s anti-Semitic. And I mentioned, ‘Possibly that is how he sees himself.’ ” “Collectio Judaica” was in essence an homage to distorted Jewish self-perceptions, an aestheticizing of their masochistic points of interest. As Zoya later put it, she needed to indicate “how Jews see themselves via the anti-Semitic gaze.”

The objects are mesmerizing. Take the Passover Haggadah. Zoya, who knew just about nothing about Jewish liturgy, wrote it herself, by hand, in a Hebrew font she invented that appears remarkably genuine. She then illuminated it in a method that mixes medieval artwork and Russian Constructivism, tossing in a number of references to Tetris, a pc sport invented within the Soviet Union. Lots of the illustrations portrayed rabbis with the our bodies of birds. This was an allusion to a well-known 14th-century Haggadah, the Birds’ Head Haggadah, which sidestepped the medieval Jewish aversion to representing the human face by changing Jews’ heads with these of birds. However Zoya reversed the order and hooked up birds’ our bodies to Jewish faces, thereby invoking an outdated anti-Semitic trope wherein Jews had been portrayed as ravens.

Animal faces within the mizrach gouache work had been based mostly on a late-Nineteenth-century anti-Semitic German postcard depicting Jews as animals, in accordance with the scholar Liliya Dashevski. The panels of one other beautiful object, an East Asian–type folding display screen, featured work of Orthodox Jewish males whose coattails flip outward like birds’ tails. Dashevski speculated that Zoya was taking part in on a secular-Israeli slur for Hasidic Jews, “penguins.” After which there have been the seder plates. Of their middle, Zoya drew Gorey-esque little boys, one trussed in rope, the opposite bare and chubby like a Renaissance putto. Round them she delicately splattered crimson paint, like drops of blood. Did the certain youngsters merely discuss with the killing of the firstborn, a part of the story of Passover, and did the drops of blood allude to the crimson wine dribbled by seder individuals onto the plate to point their sorrow at Egyptian struggling? Or was she invoking the blood libel? Sure and sure. The objects held layers of that means.

Gideon Ofrat, the artwork historian, was enchanted by “Collectio Judaica.” “This shocking, surprising, satirical anti-Semitism. It was breathtaking. It was very daring,” he informed me. He purchased a pillow—“completely achieved”—embroidered with the portrait of a big-nosed outdated man with a sack over his shoulder, an outline of the Wandering Jew, one other anti-Semitic trope. The Jewish Museum in New York now owns the Haggadah and a seder-plate set.

Zoya’s profession as a high-concept prankster thrived, however towards the top of the aughts, she determined to do one thing actually radical: study to color life once more. The push got here from a mentor she acquired throughout a stint in Berlin, Avdey Ter-Oganyan, a charismatic and transgressive Russian “motion,” or efficiency, artist with a fiery disdain for art-world norms. He inspired Zoya to shed her intellectualism and recommit herself to seeing.

However that may take follow. So Zoya went again to Israel and recognized 4 feminine artists from the previous Soviet Union who had been wanting to get out of the studio. The 5 of them went to the rougher neighborhoods of Tel Aviv, equivalent to Neve Sha’anan, the place many international staff and refugees dwell, and arrange their easels. Individuals stopped to talk or touch upon their work; some posed for portraits. After some time, the ladies determined to name themselves the New Barbizon, a tribute to the Nineteenth-century French painters who rebelled towards the claustrophobic conventions of the French Academy and painted landscapes en plein air. Zoya bought her husband, Sunny, who’s a truck driver, to drive a “Barbizon cell” so they might transport massive canvases throughout Israel. Finally they traveled so far as Leipzig, Moscow, Paris, and London.

The New Barbizon painters had been critical about portray, however their adventures had a sure performativity about them. As Zoya put it, they had been trolling. Their goal was the artwork institution, which nonetheless turned up its nostril at their old-school realism. At an enormous artwork honest in Tel Aviv referred to as Recent Paint, in 2011, they sat proper outdoors the honest on moveable chairs. They put up indicators—one in every of them learn ARTIST WITH DIPLOMA—and drew the individuals ready in line for 50 shekels a pop.

Inside a number of years, New Barbizon had change into a phenomenon. (Individuals within the artwork world “love being trolled,” Zoya mentioned.) Collectors started shopping for the ladies’s work. The New Barbizon artists had many exhibits, as a gaggle and individually; they nonetheless do.

With Zoya’s 2018 solo present on the Israel Museum, she got here full circle. “Pravda” was one of many first main cultural occasions to mirror the Russian Israeli expertise. The labels had been in Russian in addition to in Hebrew and English, which was unheard‑of. As ordinary, Zoya trafficked in stereotype, relying on type—exaggerated cartoonishness, a touch of the grotesque—to speak a spirit of satire. In spite of everything, stereotypes are a key a part of the immigrant expertise, the lens via which newcomers see and are seen. Therefore the obtuse rabbis, the cowering Uncle Yasha, and, in Aliyah of the Nineties, the bare Russian girl, presumably a prostitute, presenting herself doggy-style. In Itzik, a swarthy Mizrahi falafel-store proprietor grabs a blond Russian waitress and tries to kiss her. Unsurprisingly, some Mizrahi Jews accused Zoya of racism. Zoya rejects the cost. It’s a “commentary on racism,” she mentioned, not what she thinks of Mizrahim. “Some individuals get it; some individuals don’t get it. What can I do?”

“We rushed to the present,” Rozovsky of Haaretz informed me. She acknowledged each scene in each portray: Zoya had painted her life. Rozovsky and a good friend took a selfie in entrance of The Circumcision of Uncle Yasha, planting themselves on both facet of his penis. “It was us! We had been right here! Not in some small Russian cultural middle however in a museum.”

One afternoon throughout my go to, I bought to see Zoya’s goofy facet, as a result of Natalia Zourabova dropped by. Along with being a New Barbizon painter, she is Zoya’s greatest good friend, and collectively they’re like “two snakes in dialog,” Zoya mentioned. “If somebody ever publishes our WhatsApp, we’re useless.” The 2 of them (Zoya doing many of the speaking) informed me about efficiency items they’d dreamed up—only for enjoyable, to not really stage. One would parody this 12 months’s Met Gala, which tons of of protesters tried to overrun; the police stopped them a number of blocks away. The ladies would play celebrities, dressing up in outfits manufactured from shiny thermal blankets, and be carried dramatically up a staircase—it will invoke the doorway to the Met—on the shoulders of some sturdy males. Then they’d sprint again down the steps and play pro-Palestinian activists, protesting themselves of their position as celebrities detached to genocide. Possibly they’d ask Sunny and his mover associates to do the carrying, Zoya added, as a result of, being African, they’d insulate the ladies’s superstar characters from criticism: “They’re Indigenous to a far place.”

Indigenous is a phrase at all times lurking in Zoya’s thoughts, ready to be labored right into a darkish joke. It means “inhabiting a land earlier than colonizers got here,” and is exactly what Jewish Israelis are accused of not being—they’re allegedly the colonizers. (Those that dispute this declare counter that Jews have lived constantly on the land that’s Israel and Palestine for 1000’s of years.) Therefore, many Israelis hear Indigenous because the prelude to a requirement: “Return to the place you got here from.” However the place is that? Zoya, whose paternal great-grandparents had been shot throughout the two-day slaughter of 33,771 Jews at Babi Yar, outdoors Kyiv, has a solution. It takes the type of a overtly tasteless sketch of her and Sunny. He’s decked out like a Tintin caricature of a cannibal, in bones and a grass skirt. Zoya wears the striped pajamas of a concentration-camp inmate. It’s important to learn these portraits as hieroglyphics: Sunny = “Indigenous,” Zoya = “Auschwitz,” and collectively they’re “the Indigenous of Auschwitz.” Consider it as one other “Fuck you.”

Brash as she was, I used to be speaking with a extra subdued Zoya, she informed me. The previous 4 years have been arduous. The loneliness of COVID introduced a brand new tenderness to her work. Throughout the pandemic, she did two on-line exhibitions for her New York gallery. “Misplaced Time” (2020) sketched historic scenes of Jewish life in periods of plague in a sweetly schmaltzy idiom that jogs my memory of the kitsch my dad and mom used to hold on their partitions. “Girls Who Work” (2021) rendered the lives of intercourse staff, bare and numb and topic to violence, in a tone that’s sorrowful however permits them their dignity and fleeting moments of intimacy. After the pandemic, she mounted “The Arrival of International Professionals” (2023), oil work that inform tales from the African diaspora in Israel and Europe. One other present included fond portraits of her husband’s household and others from his hometown in Nigeria, Igwo, the place Sunny and Zoya now have a home.

The warfare in Ukraine put Zoya at a brand new take away from her previous and her household, a lot of whom nonetheless dwell within the nation. Current work of her outdated Kyiv neighborhood present Russian tanks rolling via the streets. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s formation of a far-right authorities in 2022 made left-leaning artists like Zoya really feel much more lower off from mainstream Israeli society. Since then, they’ve come to really feel that they’ve been forged out of the neighborhood of countries.

Zoya shares the nationwide anguish in regards to the hostages, grieving for them as in the event that they had been family. At some point, she informed me, she went to a park with associates, and so they noticed a typical Israeli household—“you realize, the grandpa that’s telling jokes,” and his three youngsters and their youngsters. It was, she mentioned, “a really good household that reminds you of the kibbutznik sort of household.” (Nearly all of the October 7 assaults had been on kibbutzim within the south of Israel.) Zoya and her associates had regarded on the household and mentioned to at least one one other, “This may very well be the household of the kidnapped. We have a look at them, and we’re like—” She broke off her sentence and, placing her head in her palms, began to cry.

It dumbfounded me, the crumbling of the invincible Zoya. However I used to be discovering the identical despair all over the place I went. “You aren’t even allowed to speak about it,” she continued, weeping, as a result of every time the response can be the identical: “‘Look what you might be doing in Gaza. You can not cry for what occurred to you.’ ” I felt I may virtually hear hecklers, transmogrified into spectral figures in Zoya’s head, snarling at Israel’s ache.

After which Zoya, who had so laboriously retrained herself to look, implied that the act of seeing itself had change into insufferable—not at all times, however typically. Seeing footage of lovely younger individuals on Fb, she mentioned, she couldn’t stand their magnificence, as a result of the pictures had been more likely to have been posted to commemorate those that had been killed on the Nova competition. Even seeing “your youngsters”—her youngster—was distressing, “since you think about issues.”

Zoya was nonetheless portray, after all, however her topic for the time being was, largely, life in Germany, previous and current, based mostly on wry sketches she had remodeled the course of many visits. (Sometimes, the information was so horrible that she needed to react, as when Hamas murdered six hostages on the finish of August and he or she made a sketch of one in every of them, Hersh Goldberg-Polin, and posted it on Instagram.) She informed me she had chosen Germany as a result of she had a present developing in Leipzig, however I believed that perhaps she additionally needed to avert her eyes from her fast environment. If that’s the case, Zoya can’t be the one artist in that scenario. All around the area, the current is difficult to have a look at, and the long run is ever tougher to think about.

This text seems within the November 2024 print version with the headline “What Zoya Sees.”

[ad_2]